There are so many snake species in the world today. Surprisingly few are harmfully venomous (you can learn more about that here).

Venom is really toxic saliva mainly made up of proteins and enzymes. Different species of snake will have venom specialized for their preferred prey. That venom can be categorized into four types: Proteolytic (breaks down the area surrounding the bite), Hemotoxic (affects the cardiovascular system), Neurotoxic (affects the nervous system and brain), and Cytotoxic (affects cells near the bite).

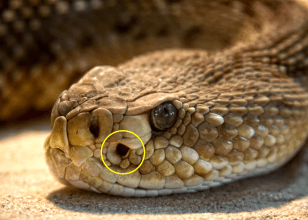

Venomous snakes produce venom in their venom glands behind the eyes on either side. Specialized muscles surround the glands so the snake can push the venom down into the fangs and inject it into its prey.

There are four groups of snake teeth: Solenoglyphous, Proteroglyphous, Opisthoglyphous, and Aglyphous.

Aglyphous teeth are the usual non-fang teeth found in both venomous and non-venomous species.

Solenoglyphous fangs can be found in the viper family (viperdae) and are some of the most advanced fangs of any venomous snake. Solenoglyphous fangs are partially hollow so the venom can go down through the tooth and be injected into the prey.

Snake skulls are very unique; they are made up of many different bones only loosely connected, rather than how a human skull is fixed together. This allows snakes to move and stretch their mouths and allow for feeding on large prey. The viper’s fangs are connected to the maxilla which is hinged, allowing the snake to extend its fangs further than it could if they were fixed.

Proteroglyphous fangs are found in the Elapid family, like Solenoglyphous fangs, Proteroglyohous fangs are also attached to the maxilla but are fixed rather than hinged. The fang (or sometimes fangs) is much smaller than the vipers. So a snake with Proteroglyphous fangs will usually bite and hold on or chew to get the venom in. They have a smaller hole for the venom to travel through but often carry highly toxic venom, some of the most potent in the world.

Spitting Cobras in the genus Naja and Hemachatus are Elapid snakes with fixed Proteroglyphous fangs. They are able to eject their venom at a distance of four to eight feet because the hollow part of their fang angles to the front rather than straight down. So the venom comes out of the front of the fangs, where the snake directs it often toward the eyes of a potential predator. This is a defense mechanism rather than for use in capturing prey.

Opisthoglyphous fangs are also known as rear fangs. They have a small grove, with less potent venom, and can be found in Colubrid snakes. They are located behind the regular Aglyphous teeth, and the snakes have to chew on their prey in order to inject any venom. Snakes with these fangs are not of any danger to humans and are often classified as non-venomous, with the exception of the Boomslang (Genus Dispholidus). Colubrid snakes with these fangs do not have true venom glands, instead, they have Duvernoy’s glands, that produce some mild venom and lack the same musculature as true venom glands.

Curious how to tell if a snake is venomous or not? You can read more about that here, and take a quiz to see how well you can tell the difference.

Sources: LifeisShortbutSnakesareLong, ReptileKnowledge, Wikipedia, NationalLibraryorMedicine,